As I have discussed previously, applying for federal trademark registration is more complicated than many believe. Indeed, even selecting the proper application to file can be confusing. In recent years, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) has made its preference for electronic filing known in no uncertain terms. However, the USPTO actually offers applicants multiple electronic application options, including the relatively recent addition of the TEAS Reduced Fee or TEAS RF application. As with the pre-existing TEAS PLUS electronic application, the new TEAS RF application requires applicants to file documents and correspond with the USPTO electronically. However, the new TEAS RF application now permits applicants to enter their own identifications of the goods and/or services covered in the application. Previously, applicants were faced with the choice of filing the more expensive regular TEAS application, which permitted “free form” descriptions of goods and services, or filing a TEAS PLUS application, which had a lower filing fee, but required applicants to use one or more of the standard goods and services identifications contained in the U.S. Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual. The filing fee for the new TEAS RF application is $275.00 per class, a significant reduction from the TEAS filing fee of $325.00 per class of goods or services. The TEAS PLUS filing fee has been reduced from $275.00 to $225.00 per class and remains a viable option for applicants whose goods or services clearly fall within the predefined identifications in the U.S. Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual. Applicants who do not wish to file and communicate with the USPTO electronically may still use the standard TEAS application, which has a filing fee of $325.00 per class. For applicants who must use paper applications, the filing fee is $375.00 per class.

0 Comments

As discussed in previous posts, the importance of properly clearing a mark before using it in commerce cannot be overstated. Indeed, failing to investigate the availability -- and registrability -- of a desired mark can lead to costly and time-consuming problems. Because most publicly known trademark cases tend to involve infringement, most individuals and businesses recognize the danger associated with infringing another party's mark. However, the concept of trademark dilution is foreign to many. In general, trademark infringement requires the unauthorized use of an existing mark (or a similar mark), which causes "likelihood of confusion" among consumers as to the source of goods or services (i.e., a consumer makes a purchase decision based on a particular brand, thinking he is purchasing the item from the intended source, when in fact it comes from a different, and typically substandard, source). Although each infringement case is unique, generally, a mark can only receive protection against competing and commonly associated goods or services. For example, if one uses the mark ACME to identify jet-powered roller skates, the owner of the mark likely could not prevent another party from using ACME to identify jelly beans. The owner should, however, be able to prevent another party from using ACME to identify jet-powered skateboards, based on the likelihood of consumer confusion. Thus, trademark infringement requires a showing that the public is likely to confuse an infringed party's goods or services with the infringing party's goods or service. Unlike infringement, trademark dilution is based on the idea that any use of a very well-known mark -- even to identify goods and services unrelated to those connected with the original mark -- will weaken or “dilute” the original mark. Broadly speaking, dilution occurs when a mark is "tarnished" or "blurred" because of the second use. Tarnishment refers to the stigma arising from the public's inaccurate association of a particular mark with another party's questionable or inferior goods or services. In other words, the perception that the mark is being used to identify certain goods or services causes damage to the reputation and goodwill of the original mark and its owner. Blurring is a broader concept, under which the mere use of a mark to identify any goods or services besides those offered by the mark's owner causes the mark to lose its distinctiveness and definitive association with the original goods or services. Although many states had antidilution statutes at the time, trademark dilution became a matter of federal law when Congress passed the Federal Trademark Dilution Act of 1995 (the "FTDA"), codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c), which was amended extensively in 2006 with the passage of the Trademark Dilution Revision Act (the "TDRA"). Under the FTDA and many similar state statutes, only "famous" marks are eligible for antidilution protection. Thus, the threshold question is whether a particular mark is "famous." Generally, for a mark to be considered famous, it must be very strong and broadly known. Under the TDRA, famous marks are those that are "widely recognized by the general consuming public of the United States" as an indication of the source of particular goods or services. In other words, a mark must be famous in general across the country, and cannot be limited to a particular geographic region or type of consumer (e.g., purchasers of automobiles). Few marks meet this strict standard for federal protection. However, under some state antidilution statutes, a mark might be subject to antidilution protection based on so-called "niche fame." The issue must be examined in the context of a particular mark, its specific use, and the applicable state law. Although trademark dilution protection extends to far fewer marks than infringement protection, it is an important concept for businesses and individuals to consider, particularly during the mark selection process. The potential for dilution of famous marks is one of several factors that trademark lawyers consider during the trademark clearance stage.  As discussed in Part 3 of this series, after it is filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”), an application for trademark registration is assigned to an Examining Attorney. The Examining Attorney first reviews the application to ensure compliance with the federal trademark statutes and the USPTO rules. Next, the Examining Attorney conducts a substantive examination of the application. The examination includes consideration of the mark’s registrability, generally, and a review of the USPTO records to determine if the registration sought would create a likelihood of confusion with any existing federally registered marks. If the examination reveals no registration impediments, the mark proceeds to publication in the Official Gazette, a weekly journal published by the USPTO containing detailed information about all marks receiving approval for registration by their respective Examining Attorneys for the relevant publication period. Publication provides notice of the pending application to the world. After publication, any party believing it will be damaged by a particular mark's registration may, within thirty days, file an opposition to the registration or request an extension of the time to oppose the registration. An opposition is similar to a proceeding in a federal court, but is held before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the "TTAB"). If no one files an opposition, or if the opposition is unsuccessful, the application will proceed and usually the mark becomes registered in due time. On the other hand, if the Examining Attorney determines that there is a minor issue with the application, he or she might contact the applicant or, if represented by counsel, the applicant’s attorney, to discuss an Examiner’s Amendment, which typically can be resolved over the telephone. However, if the Examining Attorney finds any significant issues that would prohibit registration, he or she will issue a detailed letter called an Office Action to the applicant or his or her attorney, identifying the legal impediments to registration. Similarly, any technical or procedural deficiencies in the application are typically addressed in an Office Action. The primary pitfall at this stage for many applicants (particularly those attempting to register marks without legal assistance) is failing to give due consideration to all arguments contained in the Office Action. Or worse, completely ignoring the Office Action and hoping the Examining Attorney will have a change of heart and register the mark anyway. If an Examining Attorney sends an Office Action, the applicant must take the matter seriously and file a written response within six months to avoid abandoning the application. The response must adequately address and overcome all objections under the proper legal standard or the Examining Attorney will issue a Final Refusal. In some instances, an experienced trademark attorney might be able to save an application filed previously without legal assistance through the response to the Office Action. However, because many of the issues that typically result in an Office Action can be traced to an earlier misstep in the trademark prosecution (e.g., the failure to properly clear a mark, the misidentification of good and services in the application, etc.), sometimes the problems are too significant to overcome through a response. In some instances, an applicant might be able to appeal a Final Refusal to the TTAB, or simply apply again for registration. However, before investing additional time and money after receiving a Final Refusal, it is advisable to first consult with a trademark lawyer to assess the likelihood of registration, as well as the other issues discussed throughout this series. Common Trademark Selection and Registration Pitfalls (Part 3): Application for Registration4/7/2016  After determining that a desired mark is available for use and registration (as discussed in Part 1 and Part 2 of this series), the focus next turns to preparing the application and its various components. Although rarely uniform, the order of the stages in trademark applications is fairly standard. First, the trademark owner files the application for registration. There are several options concerning the actual application form, which should be considered carefully, as not all options are available in every instance. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) has offered an electronic filing option for many years (which we will discuss in a later article), but the agency recently expanded the electronic application options, which can be confusing for the inexperienced applicant. Although discouraged and more expensive than electronic applications, the USPTO also accepts paper applications. After the USPTO receives an application for registration and determines that it meets the minimum filing requirements, the USPTO issues the application a unique serial number and assigns it to an Examining Attorney. The Examining Attorney first reviews the application to determine if it complies with the federal trademark statutes and USPTO rules. If so, he then conducts a comprehensive examination of the application, including a search for any conflicting registered marks in the USPTO system and a detailed examination of the application. An applicant should not take the application preparation lightly and must understand that errors can lead to delays, additional expense, and potentially a refusal to register a mark. Indeed, the deceptively simple appearance of the application coupled with the significant scrutiny that Examining Attorneys apply during examinations has caused problems for countless inexperienced applicants. Although the number of potential issues is too great for any comprehensive discussion, the following are some common problems. First, some applicants fail to understand that one obtains rights in a mark through actual use of the mark in commerce. Although it is possible to file a federal application based on the “intent to use” the mark in commerce, one obtains no rights until after the first actual use occurs. An applicant must identify the proper “basis” for filing the application, which generally means he is either currently using the mark in commerce or has a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce and is taking actual steps to use the mark in commerce (i.e., not simply attempting to preclude someone else from using the mark), such as market research, negotiating with suppliers or customers, etc. Another common issue is the failure to properly identify the goods or services the mark is used to identify. The application must include a proper identification of the goods and/or services. Further, if those goods and/or services are dissimilar, they most likely fall within multiple classes of goods and services. The USPTO follows the international classifications of goods and services, in which specific categories of goods and services are grouped. Depending upon the circumstances, a mark might fall into one or more of the 45 current classes, which can require a more complex and expensive application. Words really do matter when crafting the identification for a particular good or service. So much so that we will discuss this specific issue in more detail in the next installment. Another common problem is attaching an incorrect drawing or depiction of the mark to the application. An applicant must correctly identify the type of mark (e.g., word mark, graphic design, composite mark) and provide an accurate depiction of the mark. An applicant might seek broad rights in a mark by filing an application for a word mark, in which case, a “standard character” drawing is appropriate. On the other hand, the applicant might wish to protect a design or logo, in which case a “special form” drawing should be used. Improperly designating the type of registration or including an inaccurate depiction of the mark can result in certain elements of a mark being excluded from the registration or a refusal to register the mark. A similar issue can arise when selecting appropriate specimens of a mark to support the application. An applicant must provide a "specimen" that demonstrates the actual use of the mark in commerce (either in the application, if the application is based on actual use of the mark, or in a subsequent Statement of Use or Amendment to Allege Use, as appropriate, if the application is based on the intent to use). Not all specimens are proper to illustrate use for both goods and services. Here too, attaching the wrong type of specimen can delay the application process and potentially preclude registration. These are just some of the issues that can arise during the trademark application process. In the next installment of this series, we’ll cover several issues that can arise after filing, and during the pendency of, an application.  After identifying a potential mark (as discussed in Part 1 of this series) one must determine if the mark is available for use in commerce. At a minimum, this involves examining existing federal and/or state rights that other parties might have in potentially conflicting marks. During this “clearance” process, the reviewer should research a variety of sources to determine if another party is using an identical or confusingly similar mark to identify the same or related goods or services. One of the most prevalent and costly pitfalls in trademark selection and registration is the adoption and use of a mark in commerce without first clearing the mark. Some individuals and businesses consciously choose to forego clearance (often because of short-sighted time and cost considerations), while others simply are unfamiliar with the process and its importance. The primary clearance objectives are (1) to determine the existence of other registered marks that are identical or confusingly similar to the proposed mark, which likely would bar the registration of the proposed mark, and (2) assuming no such registered marks exist, to identify other potential registration objections that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) or third parties might raise during the application process. A proper clearance involves two separate steps: (1) the preliminary or “knockout” search and (2) the full clearance search. The knockout search should identify marks that would present obvious conflicts, before investing time and money in a full clearance. For instance, if one desires to use the mark COCA-COLA to identify a new beverage, a knockout search would quickly (and economically) reveal numerous existing marks containing the COCA-COLA literal element (including the COCA-COLA® word mark registration), which would bar the registration of the proposed mark. If a mark clears the preliminary search stage, the reviewer should undertake a more comprehensive full clearance search, incorporating search criteria for identical marks, marks with spelling variations, phonetic equivalents, and other similar marks appearing in USPTO and state records, published directories and reports, domain name registrations, and on the Internet. Most trademark practitioners conduct the knockout search in-house and obtain full clearance reports from established vendors specializing in comprehensive trademark searches, such as Thomson CompuMark. A trademark lawyer will work with his or her client to tailor the clearance strategy to match the applicable goods or services and relevant market. This is particularly important in the modern business world, in which the Internet permits even the smallest of companies to conduct business in the international marketplace. Certainly, one never likes to discover potentially conflicting marks -- particularly during the more expensive full search. However, the existence of a seemingly conflicting mark does not always mean a proposed mark is unavailable. Indeed, in some cases, a closer examination of the registration or application documents might reveal that what first appeared to be a conflict is a non-issue. For example, the overall commercial impression of the marks, coupled with distinctions in the applicable goods or services, might create the necessary level of distinction to permit use and registration. In other instances, the owner of a previously registered mark might no longer be using the mark. Similarly, a clearance report could identify a mark as being the subject of a pending application, while a closer examination of the USPTO record might reveal that the owner actually abandoned the application. Even in instances in which there is a bona fide conflicting mark, the respective mark owners might be able to resolve the conflict by entering into one or more appropriate agreements, for example co-existence agreements for certain territories and/or certain goods or services, licenses, or purchase agreements. However, it is only with knowledge of potentially conflicting marks that one can fully evaluate his or her position and explore these or other options. Unfortunately, even the most robust, well-developed clearance strategy cannot absolutely guarantee the absence of any conflicting marks. But a well-developed search strategy increases the chances of identifying potential conflicts before investing significant time and money in applying for registration, which is the topic of the next installment of this series.  Many entrepreneurs (and even a few lawyers) approach the adoption and registration of trademarks and service marks (collectively, “marks”) with the wrong mindset, failing to devote due consideration, time, and investment to the process. Issues can arise throughout the selection, registration, protection, and exploitation of marks. In the first installment of this multi-part series, I discuss some common problems that can arise during the mark selection stage. In future installments, I will examine some additional issues that tend to crop up in the latter stages. "What is a mark, anyway?" Most business owners understand the importance of carefully selecting and developing their marks. However, some of the most brilliant entrepreneurs still consider the investment of time and money in effective mark development to be a low priority. Too often, marks are considered nothing more than the name for certain products or services -- the functional equivalent of an identification number. Ideally, a mark should reflect the essence of the associated product or service, create a direct and positive impression in the minds of relevant consumers, and provide protection against confusingly similar marks that might divert consumers to competitors. Marks serve several fundamental purposes, including the following:

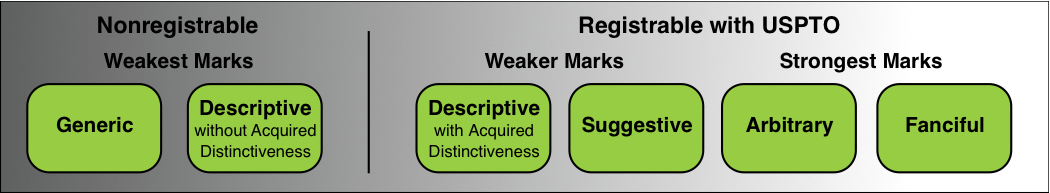

Mark Distinctiveness One mistake businesses frequently make when choosing a mark is failing to recognize that the selection process is not purely a marketing issue, but a combination of marketing and legal considerations. When developing a “short list” of potential marks, most businesses instinctively try to create a distinctive mark, whether or not it's an expressly stated objective. Essentially, a mark's distinctiveness is how well it distinguishes one’s goods or services from those available from alternative sources or competitors. When assessing potential marks, businesses sometimes fail to consider the overall strength (and protectability), focusing solely on the mark’s “catchiness,” or general memorability. A mark might be very catchy, but not very protectable, if at all. The more distinctive, the stronger the mark. A mark may be considered Generic - the common name of, or descriptor for, the good or service itself (e.g., APPLE for apples, as opposed to the same mark for computers and electronic devices); Descriptive - one that directly and immediately conveys some knowledge of the characteristics of the goods or service (e.g., PENCILS AND PAPER for a retail stationery store); Suggestive - marks suggesting some quality or ingredient of the goods or services, as opposed to actually describing the goods or services, as with descriptive marks (e.g., COPPERTONE® for sun tan oil); Arbitrary - commonly used words and/or graphic elements being used to identify goods or services for which the mark does not naturally suggest or describe an ingredient, quality, or characteristic (e.g., APPLE® for computers); or Fanciful - original, “coined” words or elements that are developed for the sole purpose of functioning as a mark (e.g., EXXON® for petroleum products). Generic marks can never become protectable, registrable marks (at least at the federal level); however, descriptive terms can be protected if they first acquire secondary meaning in the minds of consumers (i.e., the mark causes one to think of the mark owner's specific goods or services, rather than those of competitors). Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful marks are inherently distinctive and need not acquire secondary meaning to be registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”). Some brand consultants gravitate toward marks in the upper suggestive/lower arbitrary range, which can effectively combine the catchiness that their clients desire, with the increased protection that more distinctive marks provide. Mark Clearance and Other ConsiderationsAnother common and potentially costly -- sometimes financially devastating -- mark selection issue is the failure to properly clear a mark before its adoption and use in commerce. More than one company has spent significant time and money developing a great product or service, taken the goods or services to market under an uncleared mark, and only then discovered (typically after receiving a not-so-friendly "cease and desist letter") that the mark is confusingly similar to another mark. Although it is sometimes still possible to use the mark, at least to some extent, the late discovery of other, competing marks almost always creates unnecessary additional expense, delay, and aggravation.

Finally, U.S. trademark law precludes certain types of marks from federal registration, including marks consisting of immoral or deceptive matter; marks that resemble previously registered marks, such that registration would create a likelihood of confusion; marks that are simply functional (e.g., merely decorative adornments on clothing that do not serve to identify the source); and marks that are geographically descriptive. Although these issues typically arise during the application stage, which I will cover in a later article, they are critical considerations during selection and clearance. Please be sure to read the next article in this series, in which I'll discuss the mark clearance process in more detail.  I love bands. I’ve been in bands virtually my entire musical life and I can tell you firsthand, when a band is comprised of individuals who share mutual respect and a passion for their music, the experience can be great. However, almost invariably, when things go bad in a band, they go bad quickly and irreparably. Although nothing can guarantee that a band's members will always get along and keep making beautiful music together (sorry, I couldn’t resist), there are steps that bands can take to foster growth and facilitate a prompt resolution when things do go bad. One of the most common challenges that new bands encounter is that they typically are so focused on their music that they never get around to discussing how they are to operate. Emerging bands are focused initially on trying to put together their repertoire, and then they start performing and recording and just never seem to get around to formally memorializing their inner workings. Unfortunately, this often leads to confusion or, even worse, mistaken beliefs among band members. Indeed, very successful bands have operated for years with no formal agreement on such critical issues as division of income and ownership of band assets. This is a recipe for disaster that all-too-often catches up with band members eventually. If a band fails to formally organize as a business entity, it operates as a partnership by default. Although a partnership is a legitimate business structure, it might not be the best form for a particular band. Indeed, many bands choose to formally organize as corporations or limited liability companies (a/k/a "LLCs"). The choice of business structure should always be considered carefully and with the advice of legal counsel. Because of the possibility of conflicts when representing bands, lawyers should advise each band member of his or her right to retain independent counsel. Also, because the various business forms carry different tax consequences, band members should also involve their individual accountants or tax advisers in the decision-making process. Regardless of the business structure that a band ultimately adopts, its members should discuss among themselves how the band will operate. This discussion should take place very early in a band’s formation and during an official band meeting, not during a band rehearsal. Rehearsals are for rehearsing and band meetings are for conducting band business. I am convinced that if bands would devote even one-tenth of the time they spend in rehearsals for band meetings, many more bands would survive rather than deteriorate because of internal conflicts. After reaching consensus among members (assuming that all members of the band are to “own” the band), the members should memorialize their agreement in a written and properly executed document. If the band is to operate as a partnership, this will take the form of a “band partnership agreement.” If the band is to operate as a corporation, this information will be contained in a “shareholders’ (or stockholders’) agreement” and if the band is to operate as a limited liability company, the information will be put into an “operating agreement.” The following is a non-exhaustive list of some of the issues to discuss and include in the written agreement: division of ownership and voting rights; division of income; ownership of master sound recordings; writing credits and copyright ownership for musical compositions written by the band members (if applicable); ownership of trademarks and service marks, including the band name and logo and brands developed for ancillary uses, such as band merchandise; and issues related to departing band members, including the continuation of the band following such a departure, the departing member’s right to use his or her name in association with the band name after departure, and continued payments to the departing member from certain income streams. As suggested above, in many instances one individual will actually own a band -- directly, or through a separate business entity -- and will hire band members through separate employment or subcontractor agreements. This, of course, raises many other issues that should be discussed with counsel. The bottom line is that band members need to give their band’s business the consideration and time that it requires. Meet, discuss, agree, memorialize, then focus on making great music with a feeling that all is well with the world -- at least until the drummer and the lead singer’s girlfriend decide to run off together . . . wait, that’s a different story for a different article.  In the first part of this article on building an effective brand for bands and solo musical artists, I discussed some basic marketing considerations. However, in addition to marketing issues, trademark and service mark development also requires critical legal analysis. The failure to clear a band name before using it in commerce can come back to haunt a group, because under United States (and certain other countries) trademark law, one obtains rights in a mark by being the first to use it in commerce, rather than being the first to register the mark. Although it is impossible to be 100% certain that a proposed mark will not infringe upon an existing use of the same or a confusingly similar mark, one should always take steps to limit potential exposure to infringement actions. Even if a challenged mark is ultimately deemed non-infringing, the legal expense to get to that point can put most bands out of business. It is advisable to seek help early from an intellectual property ("IP") lawyer with trademark clearance and registration experience. Most IP lawyers employ a two-step clearance process. The first step is generally termed the “knockout” or preliminary search, which incorporates searches of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) records, websites, and other databases. Assuming that the knockout search comes back clear, an experienced IP lawyer will then employ the services of a third party search organization for a more robust "full" search in those geographic territories in which the mark is to be used. The full search typically expands the previously mentioned sources to state business filings, industry directories, and other proprietary databases. Obviously, this is a more expansive and more expensive approach to the clearance of a mark. However, the extra expense pales in comparison to the defense costs associated with a typical trademark infringement action or, even worse, the amount of an adverse judgment. It is also extremely difficult, if not impossible, to calculate the expense of goodwill lost when one must abandon a mark and develop a new mark "midstream" because of failing to properly clear the first mark at the outset. It is also worth mentioning that bands should discuss and reach an agreement as to who owns the band’s marks, including the band name. Band name ownership is one of many issues that should be handled in a written band partnership agreement if the band is operating as a partnership or in a shareholder or operating agreement if the band is formally organized as a corporation or limited liability company (a/k/a an "LLC"), respectively. In summary, although a band’s primary business is making great music, members should always consider the management of its IP assets, including the band name, to be a critical part of that business. Addressing clearance and registration issues early with legal counsel can help limit the risk of having to adopt a new name after spending valuable time and resources, or worse, having to change names completely and pay damages to another party because of infringement.  What’s in a name? Everything! Most people recognize the power that a strong brand carries, but few take the time to consider what a brand really is. Although not completely accurate, many consider “brand” to be synonymous with with “mark,” which Black’s Law Dictionary (7th ed.) defines as “[a] symbol, impression, or feature on something, [usually] to identify it or distinguish it from something else.” True, a mark is used to identify goods and services, but at its core, a mark represents all of the goodwill associated with a particular company, product, or service. Unfortunately, a mark can also conjure up the negative vibes that one might associate with the mark’s owner. But let’s focus on the positives. Most successful entrepreneurs recognize that their trademarks and/or service marks (together with their other intellectual property or “IP”) are among their most valuable assets. I encourage bands, individual artists, and writers -- particularly those who develop their own labels and/or music publishing companies -- to do the same. The building of a brand takes time and requires careful planning. Therefore, I always recommend consulting legal counsel who is versed in IP law well before the adoption and use of any new brand (and yes, this includes the adoption of a band or stage name, hence the title of this article), as trademark clearance and registration issues are rarely straightforward. Often, a band will begin performing under a particular name without first taking steps to clear the mark. In most cases, the band will labor in relative obscurity for a number of years, flying under the radar of any other groups that have adopted the same, or a confusingly similar, name (unless the other band undertakes the advisable practice of conducting periodic vigilance searches to detect and prevent the unauthorized use of its name -- more on this topic in a later article). However, for those talented and fortunate few, opportunities can arise that quickly propel the band onto the regional, national, or even international stage. Even bands without any appreciable commercial success can place themselves on the world’s stage rather quickly by building an Internet presence. In the next installment of this two-part article, I'll discuss some more advanced considerations regarding band trademarks and services marks.  Welcome to The Levine Entertainment Law & Business Monitor. When I set out to create this blog, I asked myself a critical question -- "How many words can I fit in the name without losing readers' attention before they get to my first post?" After weeks of intense research, I settled on six. And after significant internal conflict over whether ampersands really count, I decided to add "the" to the beginning -- an addition that I'm sure you'll agree communicates authoritativeness and class, with just enough pomposity to remind you that it's a blog written by a lawyer. But seriously, my primary goal was to create a useful source for information about the legal and business aspects of entertainment, delivered in a casual, easily understandable, and frequently irreverent style. I hope you will subscribe and share your suggestions for topics. Thanks for visiting. P.S., My research also suggested that including cat photos on my website would boost its search engine rankings, so please enjoy this picture of my assistant, Buddy. What he lacks in motivation, he more than makes up for in loyalty. |

AuthorL. Kevin Levine is the founder of L. Kevin Levine, PLLC (go figure), a boutique entertainment, copyright, trademark, and business law firm in Nashville, Tennessee. A lifelong musician who grew up in his family's music store, it was inevitable that Kevin would build his legal career in entertainment and business. Archives

June 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed