After identifying a potential mark (as discussed in Part 1 of this series) one must determine if the mark is available for use in commerce. At a minimum, this involves examining existing federal and/or state rights that other parties might have in potentially conflicting marks. During this “clearance” process, the reviewer should research a variety of sources to determine if another party is using an identical or confusingly similar mark to identify the same or related goods or services. One of the most prevalent and costly pitfalls in trademark selection and registration is the adoption and use of a mark in commerce without first clearing the mark. Some individuals and businesses consciously choose to forego clearance (often because of short-sighted time and cost considerations), while others simply are unfamiliar with the process and its importance. The primary clearance objectives are (1) to determine the existence of other registered marks that are identical or confusingly similar to the proposed mark, which likely would bar the registration of the proposed mark, and (2) assuming no such registered marks exist, to identify other potential registration objections that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) or third parties might raise during the application process. A proper clearance involves two separate steps: (1) the preliminary or “knockout” search and (2) the full clearance search. The knockout search should identify marks that would present obvious conflicts, before investing time and money in a full clearance. For instance, if one desires to use the mark COCA-COLA to identify a new beverage, a knockout search would quickly (and economically) reveal numerous existing marks containing the COCA-COLA literal element (including the COCA-COLA® word mark registration), which would bar the registration of the proposed mark. If a mark clears the preliminary search stage, the reviewer should undertake a more comprehensive full clearance search, incorporating search criteria for identical marks, marks with spelling variations, phonetic equivalents, and other similar marks appearing in USPTO and state records, published directories and reports, domain name registrations, and on the Internet. Most trademark practitioners conduct the knockout search in-house and obtain full clearance reports from established vendors specializing in comprehensive trademark searches, such as Thomson CompuMark. A trademark lawyer will work with his or her client to tailor the clearance strategy to match the applicable goods or services and relevant market. This is particularly important in the modern business world, in which the Internet permits even the smallest of companies to conduct business in the international marketplace. Certainly, one never likes to discover potentially conflicting marks -- particularly during the more expensive full search. However, the existence of a seemingly conflicting mark does not always mean a proposed mark is unavailable. Indeed, in some cases, a closer examination of the registration or application documents might reveal that what first appeared to be a conflict is a non-issue. For example, the overall commercial impression of the marks, coupled with distinctions in the applicable goods or services, might create the necessary level of distinction to permit use and registration. In other instances, the owner of a previously registered mark might no longer be using the mark. Similarly, a clearance report could identify a mark as being the subject of a pending application, while a closer examination of the USPTO record might reveal that the owner actually abandoned the application. Even in instances in which there is a bona fide conflicting mark, the respective mark owners might be able to resolve the conflict by entering into one or more appropriate agreements, for example co-existence agreements for certain territories and/or certain goods or services, licenses, or purchase agreements. However, it is only with knowledge of potentially conflicting marks that one can fully evaluate his or her position and explore these or other options. Unfortunately, even the most robust, well-developed clearance strategy cannot absolutely guarantee the absence of any conflicting marks. But a well-developed search strategy increases the chances of identifying potential conflicts before investing significant time and money in applying for registration, which is the topic of the next installment of this series.

0 Comments

Many entrepreneurs (and even a few lawyers) approach the adoption and registration of trademarks and service marks (collectively, “marks”) with the wrong mindset, failing to devote due consideration, time, and investment to the process. Issues can arise throughout the selection, registration, protection, and exploitation of marks. In the first installment of this multi-part series, I discuss some common problems that can arise during the mark selection stage. In future installments, I will examine some additional issues that tend to crop up in the latter stages. "What is a mark, anyway?" Most business owners understand the importance of carefully selecting and developing their marks. However, some of the most brilliant entrepreneurs still consider the investment of time and money in effective mark development to be a low priority. Too often, marks are considered nothing more than the name for certain products or services -- the functional equivalent of an identification number. Ideally, a mark should reflect the essence of the associated product or service, create a direct and positive impression in the minds of relevant consumers, and provide protection against confusingly similar marks that might divert consumers to competitors. Marks serve several fundamental purposes, including the following:

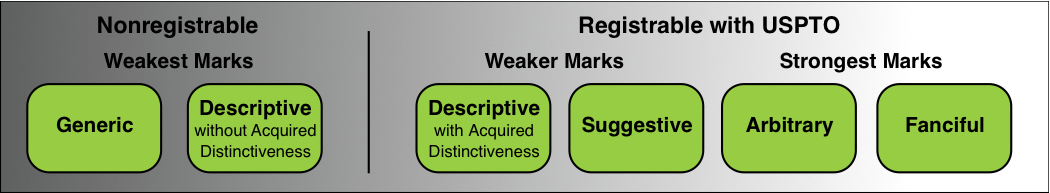

Mark Distinctiveness One mistake businesses frequently make when choosing a mark is failing to recognize that the selection process is not purely a marketing issue, but a combination of marketing and legal considerations. When developing a “short list” of potential marks, most businesses instinctively try to create a distinctive mark, whether or not it's an expressly stated objective. Essentially, a mark's distinctiveness is how well it distinguishes one’s goods or services from those available from alternative sources or competitors. When assessing potential marks, businesses sometimes fail to consider the overall strength (and protectability), focusing solely on the mark’s “catchiness,” or general memorability. A mark might be very catchy, but not very protectable, if at all. The more distinctive, the stronger the mark. A mark may be considered Generic - the common name of, or descriptor for, the good or service itself (e.g., APPLE for apples, as opposed to the same mark for computers and electronic devices); Descriptive - one that directly and immediately conveys some knowledge of the characteristics of the goods or service (e.g., PENCILS AND PAPER for a retail stationery store); Suggestive - marks suggesting some quality or ingredient of the goods or services, as opposed to actually describing the goods or services, as with descriptive marks (e.g., COPPERTONE® for sun tan oil); Arbitrary - commonly used words and/or graphic elements being used to identify goods or services for which the mark does not naturally suggest or describe an ingredient, quality, or characteristic (e.g., APPLE® for computers); or Fanciful - original, “coined” words or elements that are developed for the sole purpose of functioning as a mark (e.g., EXXON® for petroleum products). Generic marks can never become protectable, registrable marks (at least at the federal level); however, descriptive terms can be protected if they first acquire secondary meaning in the minds of consumers (i.e., the mark causes one to think of the mark owner's specific goods or services, rather than those of competitors). Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful marks are inherently distinctive and need not acquire secondary meaning to be registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”). Some brand consultants gravitate toward marks in the upper suggestive/lower arbitrary range, which can effectively combine the catchiness that their clients desire, with the increased protection that more distinctive marks provide. Mark Clearance and Other ConsiderationsAnother common and potentially costly -- sometimes financially devastating -- mark selection issue is the failure to properly clear a mark before its adoption and use in commerce. More than one company has spent significant time and money developing a great product or service, taken the goods or services to market under an uncleared mark, and only then discovered (typically after receiving a not-so-friendly "cease and desist letter") that the mark is confusingly similar to another mark. Although it is sometimes still possible to use the mark, at least to some extent, the late discovery of other, competing marks almost always creates unnecessary additional expense, delay, and aggravation.

Finally, U.S. trademark law precludes certain types of marks from federal registration, including marks consisting of immoral or deceptive matter; marks that resemble previously registered marks, such that registration would create a likelihood of confusion; marks that are simply functional (e.g., merely decorative adornments on clothing that do not serve to identify the source); and marks that are geographically descriptive. Although these issues typically arise during the application stage, which I will cover in a later article, they are critical considerations during selection and clearance. Please be sure to read the next article in this series, in which I'll discuss the mark clearance process in more detail.  “Nobody writes alone in Nashville.” That might be a slight overstatement, but most musical compositions (or "songs") -- regardless of where written -- are the product of more than one songwriter. Unfortunately, even many career songwriters do not fully understand the legal implications of co-writing. When two or more writers (or “authors” in copyright parlance) intentionally join forces to create a new song (e.g., during a writing session) the scenario is pretty straightforward. 17 U.S.C. § 201(a) provides that the resulting musical composition is a joint work if, at the time of creation, the authors intend for their contributions to be merged into a single work. Absent a written agreement (e.g., a “split letter”) to the contrary, the authors own the composition collectively as tenants-in-common, with each owning an equal and undivided interest in the entire song. In short, an “undivided interest” means that no author owns exactly what he contributed, but as a joint work, each author owns an equal share of the entire song, unless otherwise agreed in writing. Each author (or the author’s assignee -- typically a music publisher) may enter into non-exclusive licenses regarding the entire composition, subject to the continuing obligation to account to the other owners for their share of revenue from the commercial exploitation (use) of the work. Labels should obtain a mechanical license from each owner if it is a first use of the composition; however, as a practical matter, most record labels will record the song, and once the copyright owner accepts royalties, it may constitute an implied license. Few people object to having a song cut and being paid. Determining if a song is a joint work can be trickier if it was created from contributions by authors at different times, instead of during a co-writing session. For instance, if a lyricist writes lyrics and a composer sets those lyrics to music, without the lyricist’s knowledge or intent to create a joint work, the result is not likely a joint work, but rather a derivative work, which raises copyright issues beyond the scope of this article. Most courts require that each author contribute at least enough creative expression to make the contribution protectable under copyright (i.e., not merely an idea or title), and where the contributions are made at different times, there must be an agreement in writing demonstrating the parties’ intent that the contributions were intended to be part of a joint work. Also, although each joint author must contribute some creative element to the final product, each author need not contribute the same amount. Most professional songwriters adhere to the standard practice of scheduling dedicated co-writing appointments, which limits potential ambiguity over copyright ownership. When ownership of a particular work is questionable because of time or geographic distance between the authors’ contributions, it is best to clarify each author’s intent early and in writing. It's also a good idea not to wait until a song is a hit to work out an agreement, as writers who were friends when writing may become quite disagreeable when money is at stake.  I love bands. I’ve been in bands virtually my entire musical life and I can tell you firsthand, when a band is comprised of individuals who share mutual respect and a passion for their music, the experience can be great. However, almost invariably, when things go bad in a band, they go bad quickly and irreparably. Although nothing can guarantee that a band's members will always get along and keep making beautiful music together (sorry, I couldn’t resist), there are steps that bands can take to foster growth and facilitate a prompt resolution when things do go bad. One of the most common challenges that new bands encounter is that they typically are so focused on their music that they never get around to discussing how they are to operate. Emerging bands are focused initially on trying to put together their repertoire, and then they start performing and recording and just never seem to get around to formally memorializing their inner workings. Unfortunately, this often leads to confusion or, even worse, mistaken beliefs among band members. Indeed, very successful bands have operated for years with no formal agreement on such critical issues as division of income and ownership of band assets. This is a recipe for disaster that all-too-often catches up with band members eventually. If a band fails to formally organize as a business entity, it operates as a partnership by default. Although a partnership is a legitimate business structure, it might not be the best form for a particular band. Indeed, many bands choose to formally organize as corporations or limited liability companies (a/k/a "LLCs"). The choice of business structure should always be considered carefully and with the advice of legal counsel. Because of the possibility of conflicts when representing bands, lawyers should advise each band member of his or her right to retain independent counsel. Also, because the various business forms carry different tax consequences, band members should also involve their individual accountants or tax advisers in the decision-making process. Regardless of the business structure that a band ultimately adopts, its members should discuss among themselves how the band will operate. This discussion should take place very early in a band’s formation and during an official band meeting, not during a band rehearsal. Rehearsals are for rehearsing and band meetings are for conducting band business. I am convinced that if bands would devote even one-tenth of the time they spend in rehearsals for band meetings, many more bands would survive rather than deteriorate because of internal conflicts. After reaching consensus among members (assuming that all members of the band are to “own” the band), the members should memorialize their agreement in a written and properly executed document. If the band is to operate as a partnership, this will take the form of a “band partnership agreement.” If the band is to operate as a corporation, this information will be contained in a “shareholders’ (or stockholders’) agreement” and if the band is to operate as a limited liability company, the information will be put into an “operating agreement.” The following is a non-exhaustive list of some of the issues to discuss and include in the written agreement: division of ownership and voting rights; division of income; ownership of master sound recordings; writing credits and copyright ownership for musical compositions written by the band members (if applicable); ownership of trademarks and service marks, including the band name and logo and brands developed for ancillary uses, such as band merchandise; and issues related to departing band members, including the continuation of the band following such a departure, the departing member’s right to use his or her name in association with the band name after departure, and continued payments to the departing member from certain income streams. As suggested above, in many instances one individual will actually own a band -- directly, or through a separate business entity -- and will hire band members through separate employment or subcontractor agreements. This, of course, raises many other issues that should be discussed with counsel. The bottom line is that band members need to give their band’s business the consideration and time that it requires. Meet, discuss, agree, memorialize, then focus on making great music with a feeling that all is well with the world -- at least until the drummer and the lead singer’s girlfriend decide to run off together . . . wait, that’s a different story for a different article.  Many years ago, a client asked me to prepare an agreement. For obvious reasons, I cannot go into detail, however when we met to discuss the draft agreement, my client first commented on how professional the agreement looked (always appreciated), but then asked, “is all this really necessary?” She was referring to the inclusion of certain provisions that she was afraid might “scare off” the other party. In my practice, other clients have asked similar questions. In fact, over the years, I have encountered more than one individual/business that had entered into previous "handshake" agreements -- with varying degrees of success. Of course, perceived “nitpicking” by lawyers is the subject of many jokes (and sometimes accurate observations, but we won’t go there). However, there are usually legitimate reasons to include certain provisions in agreements, even if the parties themselves don’t realize it. For example, most entertainment deals implicitly involve copyright licenses or acquisitions. This frequently requires certain language to be in writing to be effective and enforceable. It is also critical to ensure that the parties’ entire agreement is accurately memorialized in writing, in case a court must interpret it at some point in the future. Certainly, a written agreement can grow to unnecessary detail and length, but that is not the goal of most lawyers. When negotiating any deal, the parties should discuss with their respective lawyers the written requirements and never assume that a simple deal memo -- or worse, no written agreement at all -- will suffice. Most lawyers would rather work with a concise agreement that addresses all of the critical issues involved in a particular deal; however, this is not always possible. |

AuthorL. Kevin Levine is the founder of L. Kevin Levine, PLLC (go figure), a boutique entertainment, copyright, trademark, and business law firm in Nashville, Tennessee. A lifelong musician who grew up in his family's music store, it was inevitable that Kevin would build his legal career in entertainment and business. Archives

June 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed