As I have discussed previously, applying for federal trademark registration is more complicated than many believe. Indeed, even selecting the proper application to file can be confusing. In recent years, the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) has made its preference for electronic filing known in no uncertain terms. However, the USPTO actually offers applicants multiple electronic application options, including the relatively recent addition of the TEAS Reduced Fee or TEAS RF application. As with the pre-existing TEAS PLUS electronic application, the new TEAS RF application requires applicants to file documents and correspond with the USPTO electronically. However, the new TEAS RF application now permits applicants to enter their own identifications of the goods and/or services covered in the application. Previously, applicants were faced with the choice of filing the more expensive regular TEAS application, which permitted “free form” descriptions of goods and services, or filing a TEAS PLUS application, which had a lower filing fee, but required applicants to use one or more of the standard goods and services identifications contained in the U.S. Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual. The filing fee for the new TEAS RF application is $275.00 per class, a significant reduction from the TEAS filing fee of $325.00 per class of goods or services. The TEAS PLUS filing fee has been reduced from $275.00 to $225.00 per class and remains a viable option for applicants whose goods or services clearly fall within the predefined identifications in the U.S. Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual. Applicants who do not wish to file and communicate with the USPTO electronically may still use the standard TEAS application, which has a filing fee of $325.00 per class. For applicants who must use paper applications, the filing fee is $375.00 per class.

0 Comments

As discussed in the first part of this series, when first faced with a dispute, band members should carefully review the group’s governing agreement (usually a band partnership agreement, operating agreement, or set of bylaws, depending upon the group’s structure), assuming one exists. Among other things, this document should include a procedure for resolving disputes, and specify the members’ rights and obligations to the group and each other if a dispute arises. Unfortunately, many groups never get around to discussing — let alone preparing — a written agreement. In those instances, state law will dictate the parties’ rights and duties. Laws and their application can vary greatly among the states and, even in a single state, the specific legal rights and obligations of individual members might differ greatly from one entity type to another (e.g., partnership, limited liability company, or corporation). Further complicating matters, all disputes are fact-based. Although two groups might have similar types of disputes, generally (e.g., the lead guitarist decides he doesn’t like the drummer any more — trust me, it happens), rarely do two isolated disputes stem from exactly the same facts or circumstances (e.g., the guitarist has evidence that the drummer is embezzling from the band vs. the guitarist’s girlfriend is “pretty sure” the drummer winked at her when the guitarist wasn’t looking). Thus, determining and applying the relevant law to a particular dispute can be complex and is a concept beyond the scope of this article. Group members who find themselves in a dispute without the benefit of a band member agreement owe it to themselves and their families to consult with independent legal counsel before taking actions that might impact their rights (including potential future income) or obligations (including potential expense and/or liability to the group, other members, third parties with whom the band has existing agreements, etc.). In the next installment, I’ll discuss possible options for moving forward toward resolution.  Throughout history, musical groups have formed, broken up for various reasons, sometimes reformed (in various incarnations), and frequently broken up again. It happens at all levels of the music industry, from your brother's garage band to the Beatles, Sonny and Cher, and the Eagles (multiple times). I'm neither a divorce lawyer, nor a marriage counselor, so don't ask me why it happens, it just does. Fortunately, not all disputes lead to a breakup and many issues that groups frequently encounter can be resolved through good faith discussion. However, should the members reach an impasse, the suggestions discussed in this series can help move the members toward resolution, even if the ultimate "resolution" is dissolving the group. Above all, the members should not ignore the issue, particularly if it is time-sensitive or affects the rights of outside parties (e.g., existing contracts for future services). Even issues that are not specifically time-sensitive deserve timely consideration. Aside from the potential negative impact on the group's business, leaving an issue open for an extended period can foster suspicion and animosity among members. Also, issues that might seem insignificant to certain members might be extremely important to others. Members should keep the lines of communication open and strive to maintain civility. Assuming one exists, members should carefully review the band partnership agreement (or, if the group is formally organized as a limited liability company (a/k/a an "LLC") or corporation, the operating agreement or bylaws, respectively) for guidance on the specific issues in dispute, as well as the procedure for dispute resolution. Please see my previous article on band agreements for more information. It might also be necessary to consult applicable state statutes to fill any gaps not provided for in a written agreement or if there is no agreement. In the next installment, I'll discuss some more formal steps for dispute resolution.  As discussed in previous posts, the importance of properly clearing a mark before using it in commerce cannot be overstated. Indeed, failing to investigate the availability -- and registrability -- of a desired mark can lead to costly and time-consuming problems. Because most publicly known trademark cases tend to involve infringement, most individuals and businesses recognize the danger associated with infringing another party's mark. However, the concept of trademark dilution is foreign to many. In general, trademark infringement requires the unauthorized use of an existing mark (or a similar mark), which causes "likelihood of confusion" among consumers as to the source of goods or services (i.e., a consumer makes a purchase decision based on a particular brand, thinking he is purchasing the item from the intended source, when in fact it comes from a different, and typically substandard, source). Although each infringement case is unique, generally, a mark can only receive protection against competing and commonly associated goods or services. For example, if one uses the mark ACME to identify jet-powered roller skates, the owner of the mark likely could not prevent another party from using ACME to identify jelly beans. The owner should, however, be able to prevent another party from using ACME to identify jet-powered skateboards, based on the likelihood of consumer confusion. Thus, trademark infringement requires a showing that the public is likely to confuse an infringed party's goods or services with the infringing party's goods or service. Unlike infringement, trademark dilution is based on the idea that any use of a very well-known mark -- even to identify goods and services unrelated to those connected with the original mark -- will weaken or “dilute” the original mark. Broadly speaking, dilution occurs when a mark is "tarnished" or "blurred" because of the second use. Tarnishment refers to the stigma arising from the public's inaccurate association of a particular mark with another party's questionable or inferior goods or services. In other words, the perception that the mark is being used to identify certain goods or services causes damage to the reputation and goodwill of the original mark and its owner. Blurring is a broader concept, under which the mere use of a mark to identify any goods or services besides those offered by the mark's owner causes the mark to lose its distinctiveness and definitive association with the original goods or services. Although many states had antidilution statutes at the time, trademark dilution became a matter of federal law when Congress passed the Federal Trademark Dilution Act of 1995 (the "FTDA"), codified at 15 U.S.C. § 1125(c), which was amended extensively in 2006 with the passage of the Trademark Dilution Revision Act (the "TDRA"). Under the FTDA and many similar state statutes, only "famous" marks are eligible for antidilution protection. Thus, the threshold question is whether a particular mark is "famous." Generally, for a mark to be considered famous, it must be very strong and broadly known. Under the TDRA, famous marks are those that are "widely recognized by the general consuming public of the United States" as an indication of the source of particular goods or services. In other words, a mark must be famous in general across the country, and cannot be limited to a particular geographic region or type of consumer (e.g., purchasers of automobiles). Few marks meet this strict standard for federal protection. However, under some state antidilution statutes, a mark might be subject to antidilution protection based on so-called "niche fame." The issue must be examined in the context of a particular mark, its specific use, and the applicable state law. Although trademark dilution protection extends to far fewer marks than infringement protection, it is an important concept for businesses and individuals to consider, particularly during the mark selection process. The potential for dilution of famous marks is one of several factors that trademark lawyers consider during the trademark clearance stage.  Years ago, during a music publishing seminar at which I was a presenter, a songwriter asked, “Why do I even need a music publisher? Couldn’t I just do what a music publisher does, myself?” My simple response was “will you?” It is generally true that of all the players in the music industry, the role of music publisher has one of the lowest thresholds to entry. Indeed, a financially successful music publisher’s stock in trade can sometimes be contained in a single desk drawer. However, that does not mean the job is easy or inexpensive, it just means that there are relatively few required steps for a company (or individual) to accurately call itself a "music publisher." If you are a beginning songwriter with one original song in your catalog and have not assigned any of your rights in that song to someone else, then congratulations, you are technically your own music publisher. Songwriters frequently receive advice -- solicited or otherwise -- from “concerned” individuals (including fellow writers, family members, friends, rabbis, etc.) that they should never, under any circumstances, “give” their copyrights to anyone. And, because the vast majority of publishing deals involve the assignment of copyright to the publisher, some consider music publishing inherently evil. Of course, it is never a good idea to enter into an agreement with just any publisher who is willing to sign you, simply so you can brag to your family and friends that you signed a publishing deal. An experienced music publisher should bring to the table at least four attributes that many songwriters lack: (1) an understanding of the music publishing business, including both the publisher’s traditional and developing roles in the larger music industry; (2) a set of established business practices and procedures to effectively manage a catalog and explore exploitation opportunities; (3) existing relationships in the industry; and (4) a relentless drive to both create a successful music publishing business and advance the careers of its signed writers. Notice that the last item does not say “a relentless drive to write great songs” -- that's the songwriter’s job. Writers who do not feel the same level of excitement about building a publishing business as they do about songwriting usually are better served by finding an effective publisher to fill that role. OK, I know what you’re thinking: “I thought the whole point of this article was to help musicians who decide to ‘do it themselves.’ Why are you telling me I need to have a music publisher?” Well, I’m not telling you that you absolutely have to find a music publisher to achieve success as a songwriter, nor am I trying to discourage you from developing your own music publishing company. However, I do encourage those entrepreneurial writers who make the decision to take on the role of music publisher to learn as much about the business as possible and to seek help when necessary. We all know the cliché, “knowledge is power,” and It definitely rings true in the music publishing world. Many great books on the subject are available, including Making Music Make Money: An Insider’s Guide to Becoming Your Own Music Publisher by Eric Beall and The Plain & Simple Guide to Music Publishing by Randal Wixen. Also, do not overlook Don Passman’s great, plain-English discussion of music publishing in his authoritative book, All You Need To Know About The Music Business, or Jeff and Todd Brabec’s detailed coverage in their book, Music Money and Success: The Insider’s Guide to Making Money in the Music Business. All of these books are available through most bookstores and online (be sure to confirm that you are purchasing the most recent edition). As a parting thought, one of the traits that distinguishes successful entrepreneurs in any industry is the ability to recognize one’s own strengths and weaknesses. Most successful entrepreneurs humbly admit that, as mere mortals, they cannot possibly do everything themselves. Delegation of certain tasks to others who are better skilled in particular areas is a reality of the business world. Even seasoned music publishers sometimes enter into administration agreements with other publishing companies that are better able to perform administrative functions, leaving the non-administrative publisher free to concentrate on creative development and seeking exploitation. Finally, although entrepreneurial songwriters certainly can acquire knowledge of the publishing business, established music publishers are already in the game, and they can sometimes open doors that might otherwise remain closed to a songwriter just getting started as a publisher. Regardless of the path you choose, you owe it to yourself and your music to make an informed decision.  Most business owners and executives have at least heard of the "big three" areas of intellectual property -- copyrights, trademarks, and patents -- although they might not fully understand the distinctions. However, trade secret law remains a foreign concept to most people, despite its important role in business. Trade secret protection is based on state law, with no federal equivalent. Thus, the definition of a trade secret and the degree of protection afforded to trade secrets varies among the states. This, coupled with the very fact-sensitive nature of trade secret cases, means that information that might be subject to trade secret protection in some states might not enjoy similar protection in others. As a general matter, a trade secret is information (e.g., a film treatment, manufacturing process, inventory system, or sales program) created by a company or individual that is not generally known to others and can provide its creator or owner with a competitive advantage. However, simply calling proprietary information a "trade secret" does not automatically make it subject to protection. Indeed, for something to legally qualify as a trade secret, its owners must take reasonable steps to protect the information. It is a prudent practice for companies to develop systems for asserting trade secret protection in their proprietary information and consistently following written procedures governing the dissemination of information considered or containing trade secrets. This might sound easy, but it actually requires careful planning and diligent implementation. Individuals and companies engaged in entertainment and other industries frequently share proprietary information with other parties. For example, a production company might send a treatment or script to other parties when securing talent for a film project. Similarly, an inventor or designer might need to share a schematic or CAD file with a manufacturer or part supplier during the sourcing or manufacturing process. At any time, many outside individuals and companies might have access to one’s confidential information. Parties engaged in business activities often use confidentiality agreements or non-disclosure agreements (often referred to as "NDAs"). At their core, non-disclosure agreements contractually bind recipients of confidential information not to disclose or use the information without the owner’s authorization, and to use it only for the purposes specified in the agreement. Among other things, a non-disclosure agreement should clearly define what information is and is not protected, the time frame for protection, and the permitted uses of the information. Employers also use non-disclosure agreements, as well as confidentiality provisions in comprehensive employment agreements, to protect against current and past employees disclosing confidential information. It is also a good practice to use non-disclosure agreements when inviting visitors to facilities if there is a chance that they might have access to proprietary information.  As discussed in Part 3 of this series, after it is filed with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”), an application for trademark registration is assigned to an Examining Attorney. The Examining Attorney first reviews the application to ensure compliance with the federal trademark statutes and the USPTO rules. Next, the Examining Attorney conducts a substantive examination of the application. The examination includes consideration of the mark’s registrability, generally, and a review of the USPTO records to determine if the registration sought would create a likelihood of confusion with any existing federally registered marks. If the examination reveals no registration impediments, the mark proceeds to publication in the Official Gazette, a weekly journal published by the USPTO containing detailed information about all marks receiving approval for registration by their respective Examining Attorneys for the relevant publication period. Publication provides notice of the pending application to the world. After publication, any party believing it will be damaged by a particular mark's registration may, within thirty days, file an opposition to the registration or request an extension of the time to oppose the registration. An opposition is similar to a proceeding in a federal court, but is held before the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (the "TTAB"). If no one files an opposition, or if the opposition is unsuccessful, the application will proceed and usually the mark becomes registered in due time. On the other hand, if the Examining Attorney determines that there is a minor issue with the application, he or she might contact the applicant or, if represented by counsel, the applicant’s attorney, to discuss an Examiner’s Amendment, which typically can be resolved over the telephone. However, if the Examining Attorney finds any significant issues that would prohibit registration, he or she will issue a detailed letter called an Office Action to the applicant or his or her attorney, identifying the legal impediments to registration. Similarly, any technical or procedural deficiencies in the application are typically addressed in an Office Action. The primary pitfall at this stage for many applicants (particularly those attempting to register marks without legal assistance) is failing to give due consideration to all arguments contained in the Office Action. Or worse, completely ignoring the Office Action and hoping the Examining Attorney will have a change of heart and register the mark anyway. If an Examining Attorney sends an Office Action, the applicant must take the matter seriously and file a written response within six months to avoid abandoning the application. The response must adequately address and overcome all objections under the proper legal standard or the Examining Attorney will issue a Final Refusal. In some instances, an experienced trademark attorney might be able to save an application filed previously without legal assistance through the response to the Office Action. However, because many of the issues that typically result in an Office Action can be traced to an earlier misstep in the trademark prosecution (e.g., the failure to properly clear a mark, the misidentification of good and services in the application, etc.), sometimes the problems are too significant to overcome through a response. In some instances, an applicant might be able to appeal a Final Refusal to the TTAB, or simply apply again for registration. However, before investing additional time and money after receiving a Final Refusal, it is advisable to first consult with a trademark lawyer to assess the likelihood of registration, as well as the other issues discussed throughout this series. Common Trademark Selection and Registration Pitfalls (Part 3): Application for Registration4/7/2016  After determining that a desired mark is available for use and registration (as discussed in Part 1 and Part 2 of this series), the focus next turns to preparing the application and its various components. Although rarely uniform, the order of the stages in trademark applications is fairly standard. First, the trademark owner files the application for registration. There are several options concerning the actual application form, which should be considered carefully, as not all options are available in every instance. The United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) has offered an electronic filing option for many years (which we will discuss in a later article), but the agency recently expanded the electronic application options, which can be confusing for the inexperienced applicant. Although discouraged and more expensive than electronic applications, the USPTO also accepts paper applications. After the USPTO receives an application for registration and determines that it meets the minimum filing requirements, the USPTO issues the application a unique serial number and assigns it to an Examining Attorney. The Examining Attorney first reviews the application to determine if it complies with the federal trademark statutes and USPTO rules. If so, he then conducts a comprehensive examination of the application, including a search for any conflicting registered marks in the USPTO system and a detailed examination of the application. An applicant should not take the application preparation lightly and must understand that errors can lead to delays, additional expense, and potentially a refusal to register a mark. Indeed, the deceptively simple appearance of the application coupled with the significant scrutiny that Examining Attorneys apply during examinations has caused problems for countless inexperienced applicants. Although the number of potential issues is too great for any comprehensive discussion, the following are some common problems. First, some applicants fail to understand that one obtains rights in a mark through actual use of the mark in commerce. Although it is possible to file a federal application based on the “intent to use” the mark in commerce, one obtains no rights until after the first actual use occurs. An applicant must identify the proper “basis” for filing the application, which generally means he is either currently using the mark in commerce or has a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce and is taking actual steps to use the mark in commerce (i.e., not simply attempting to preclude someone else from using the mark), such as market research, negotiating with suppliers or customers, etc. Another common issue is the failure to properly identify the goods or services the mark is used to identify. The application must include a proper identification of the goods and/or services. Further, if those goods and/or services are dissimilar, they most likely fall within multiple classes of goods and services. The USPTO follows the international classifications of goods and services, in which specific categories of goods and services are grouped. Depending upon the circumstances, a mark might fall into one or more of the 45 current classes, which can require a more complex and expensive application. Words really do matter when crafting the identification for a particular good or service. So much so that we will discuss this specific issue in more detail in the next installment. Another common problem is attaching an incorrect drawing or depiction of the mark to the application. An applicant must correctly identify the type of mark (e.g., word mark, graphic design, composite mark) and provide an accurate depiction of the mark. An applicant might seek broad rights in a mark by filing an application for a word mark, in which case, a “standard character” drawing is appropriate. On the other hand, the applicant might wish to protect a design or logo, in which case a “special form” drawing should be used. Improperly designating the type of registration or including an inaccurate depiction of the mark can result in certain elements of a mark being excluded from the registration or a refusal to register the mark. A similar issue can arise when selecting appropriate specimens of a mark to support the application. An applicant must provide a "specimen" that demonstrates the actual use of the mark in commerce (either in the application, if the application is based on actual use of the mark, or in a subsequent Statement of Use or Amendment to Allege Use, as appropriate, if the application is based on the intent to use). Not all specimens are proper to illustrate use for both goods and services. Here too, attaching the wrong type of specimen can delay the application process and potentially preclude registration. These are just some of the issues that can arise during the trademark application process. In the next installment of this series, we’ll cover several issues that can arise after filing, and during the pendency of, an application.  After identifying a potential mark (as discussed in Part 1 of this series) one must determine if the mark is available for use in commerce. At a minimum, this involves examining existing federal and/or state rights that other parties might have in potentially conflicting marks. During this “clearance” process, the reviewer should research a variety of sources to determine if another party is using an identical or confusingly similar mark to identify the same or related goods or services. One of the most prevalent and costly pitfalls in trademark selection and registration is the adoption and use of a mark in commerce without first clearing the mark. Some individuals and businesses consciously choose to forego clearance (often because of short-sighted time and cost considerations), while others simply are unfamiliar with the process and its importance. The primary clearance objectives are (1) to determine the existence of other registered marks that are identical or confusingly similar to the proposed mark, which likely would bar the registration of the proposed mark, and (2) assuming no such registered marks exist, to identify other potential registration objections that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”) or third parties might raise during the application process. A proper clearance involves two separate steps: (1) the preliminary or “knockout” search and (2) the full clearance search. The knockout search should identify marks that would present obvious conflicts, before investing time and money in a full clearance. For instance, if one desires to use the mark COCA-COLA to identify a new beverage, a knockout search would quickly (and economically) reveal numerous existing marks containing the COCA-COLA literal element (including the COCA-COLA® word mark registration), which would bar the registration of the proposed mark. If a mark clears the preliminary search stage, the reviewer should undertake a more comprehensive full clearance search, incorporating search criteria for identical marks, marks with spelling variations, phonetic equivalents, and other similar marks appearing in USPTO and state records, published directories and reports, domain name registrations, and on the Internet. Most trademark practitioners conduct the knockout search in-house and obtain full clearance reports from established vendors specializing in comprehensive trademark searches, such as Thomson CompuMark. A trademark lawyer will work with his or her client to tailor the clearance strategy to match the applicable goods or services and relevant market. This is particularly important in the modern business world, in which the Internet permits even the smallest of companies to conduct business in the international marketplace. Certainly, one never likes to discover potentially conflicting marks -- particularly during the more expensive full search. However, the existence of a seemingly conflicting mark does not always mean a proposed mark is unavailable. Indeed, in some cases, a closer examination of the registration or application documents might reveal that what first appeared to be a conflict is a non-issue. For example, the overall commercial impression of the marks, coupled with distinctions in the applicable goods or services, might create the necessary level of distinction to permit use and registration. In other instances, the owner of a previously registered mark might no longer be using the mark. Similarly, a clearance report could identify a mark as being the subject of a pending application, while a closer examination of the USPTO record might reveal that the owner actually abandoned the application. Even in instances in which there is a bona fide conflicting mark, the respective mark owners might be able to resolve the conflict by entering into one or more appropriate agreements, for example co-existence agreements for certain territories and/or certain goods or services, licenses, or purchase agreements. However, it is only with knowledge of potentially conflicting marks that one can fully evaluate his or her position and explore these or other options. Unfortunately, even the most robust, well-developed clearance strategy cannot absolutely guarantee the absence of any conflicting marks. But a well-developed search strategy increases the chances of identifying potential conflicts before investing significant time and money in applying for registration, which is the topic of the next installment of this series.  Many entrepreneurs (and even a few lawyers) approach the adoption and registration of trademarks and service marks (collectively, “marks”) with the wrong mindset, failing to devote due consideration, time, and investment to the process. Issues can arise throughout the selection, registration, protection, and exploitation of marks. In the first installment of this multi-part series, I discuss some common problems that can arise during the mark selection stage. In future installments, I will examine some additional issues that tend to crop up in the latter stages. "What is a mark, anyway?" Most business owners understand the importance of carefully selecting and developing their marks. However, some of the most brilliant entrepreneurs still consider the investment of time and money in effective mark development to be a low priority. Too often, marks are considered nothing more than the name for certain products or services -- the functional equivalent of an identification number. Ideally, a mark should reflect the essence of the associated product or service, create a direct and positive impression in the minds of relevant consumers, and provide protection against confusingly similar marks that might divert consumers to competitors. Marks serve several fundamental purposes, including the following:

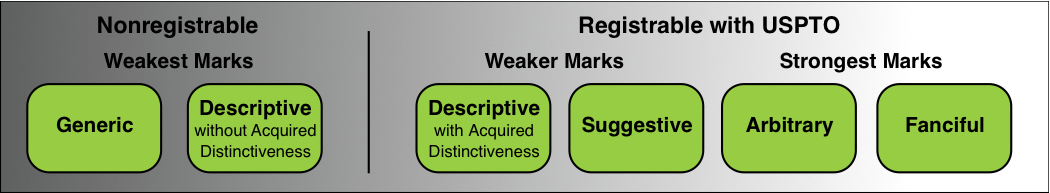

Mark Distinctiveness One mistake businesses frequently make when choosing a mark is failing to recognize that the selection process is not purely a marketing issue, but a combination of marketing and legal considerations. When developing a “short list” of potential marks, most businesses instinctively try to create a distinctive mark, whether or not it's an expressly stated objective. Essentially, a mark's distinctiveness is how well it distinguishes one’s goods or services from those available from alternative sources or competitors. When assessing potential marks, businesses sometimes fail to consider the overall strength (and protectability), focusing solely on the mark’s “catchiness,” or general memorability. A mark might be very catchy, but not very protectable, if at all. The more distinctive, the stronger the mark. A mark may be considered Generic - the common name of, or descriptor for, the good or service itself (e.g., APPLE for apples, as opposed to the same mark for computers and electronic devices); Descriptive - one that directly and immediately conveys some knowledge of the characteristics of the goods or service (e.g., PENCILS AND PAPER for a retail stationery store); Suggestive - marks suggesting some quality or ingredient of the goods or services, as opposed to actually describing the goods or services, as with descriptive marks (e.g., COPPERTONE® for sun tan oil); Arbitrary - commonly used words and/or graphic elements being used to identify goods or services for which the mark does not naturally suggest or describe an ingredient, quality, or characteristic (e.g., APPLE® for computers); or Fanciful - original, “coined” words or elements that are developed for the sole purpose of functioning as a mark (e.g., EXXON® for petroleum products). Generic marks can never become protectable, registrable marks (at least at the federal level); however, descriptive terms can be protected if they first acquire secondary meaning in the minds of consumers (i.e., the mark causes one to think of the mark owner's specific goods or services, rather than those of competitors). Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful marks are inherently distinctive and need not acquire secondary meaning to be registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (the “USPTO”). Some brand consultants gravitate toward marks in the upper suggestive/lower arbitrary range, which can effectively combine the catchiness that their clients desire, with the increased protection that more distinctive marks provide. Mark Clearance and Other ConsiderationsAnother common and potentially costly -- sometimes financially devastating -- mark selection issue is the failure to properly clear a mark before its adoption and use in commerce. More than one company has spent significant time and money developing a great product or service, taken the goods or services to market under an uncleared mark, and only then discovered (typically after receiving a not-so-friendly "cease and desist letter") that the mark is confusingly similar to another mark. Although it is sometimes still possible to use the mark, at least to some extent, the late discovery of other, competing marks almost always creates unnecessary additional expense, delay, and aggravation.

Finally, U.S. trademark law precludes certain types of marks from federal registration, including marks consisting of immoral or deceptive matter; marks that resemble previously registered marks, such that registration would create a likelihood of confusion; marks that are simply functional (e.g., merely decorative adornments on clothing that do not serve to identify the source); and marks that are geographically descriptive. Although these issues typically arise during the application stage, which I will cover in a later article, they are critical considerations during selection and clearance. Please be sure to read the next article in this series, in which I'll discuss the mark clearance process in more detail. |

AuthorL. Kevin Levine is the founder of L. Kevin Levine, PLLC (go figure), a boutique entertainment, copyright, trademark, and business law firm in Nashville, Tennessee. A lifelong musician who grew up in his family's music store, it was inevitable that Kevin would build his legal career in entertainment and business. Archives

June 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed